Formula One News

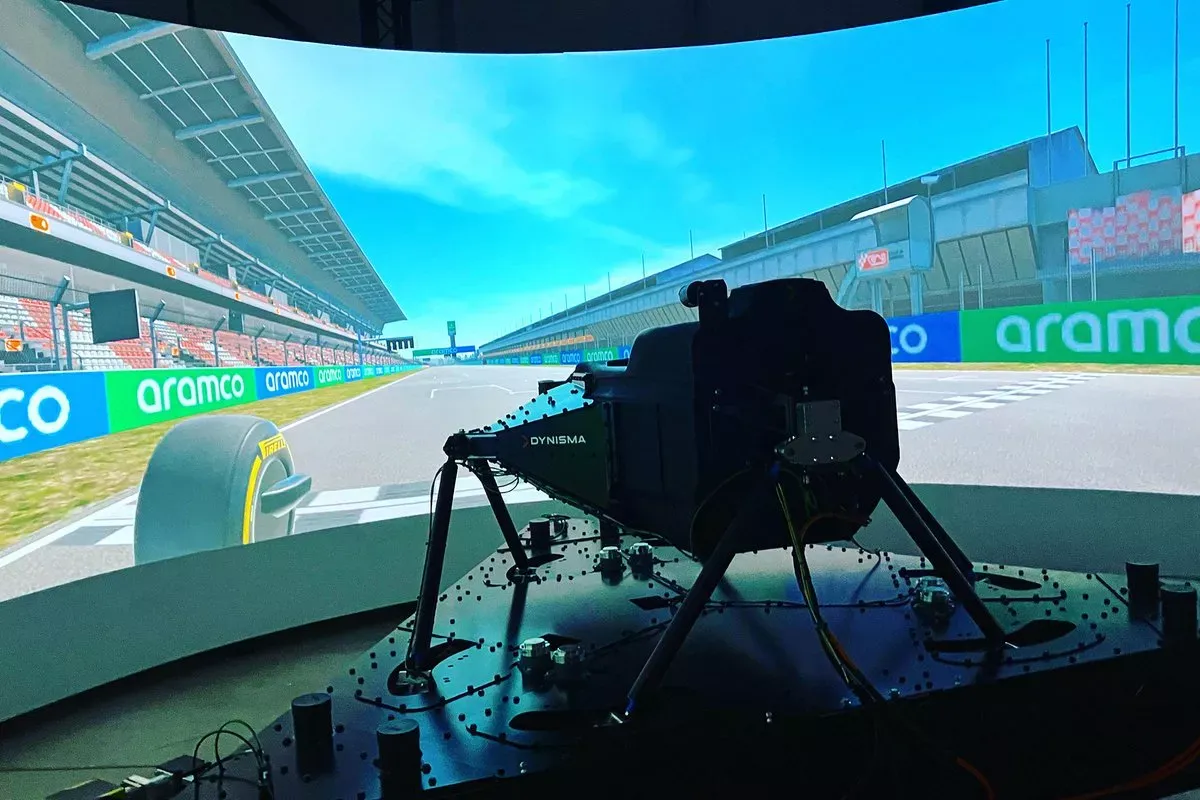

Simulators have become an essential tool in the complex set-up that is a Formula 1's team development programme. Jonathan Noble got behind the wheel of Dynisma's state-of-the-art DMG-1, a simulator that anyone with a large cheque can buy. Here's his experience with it

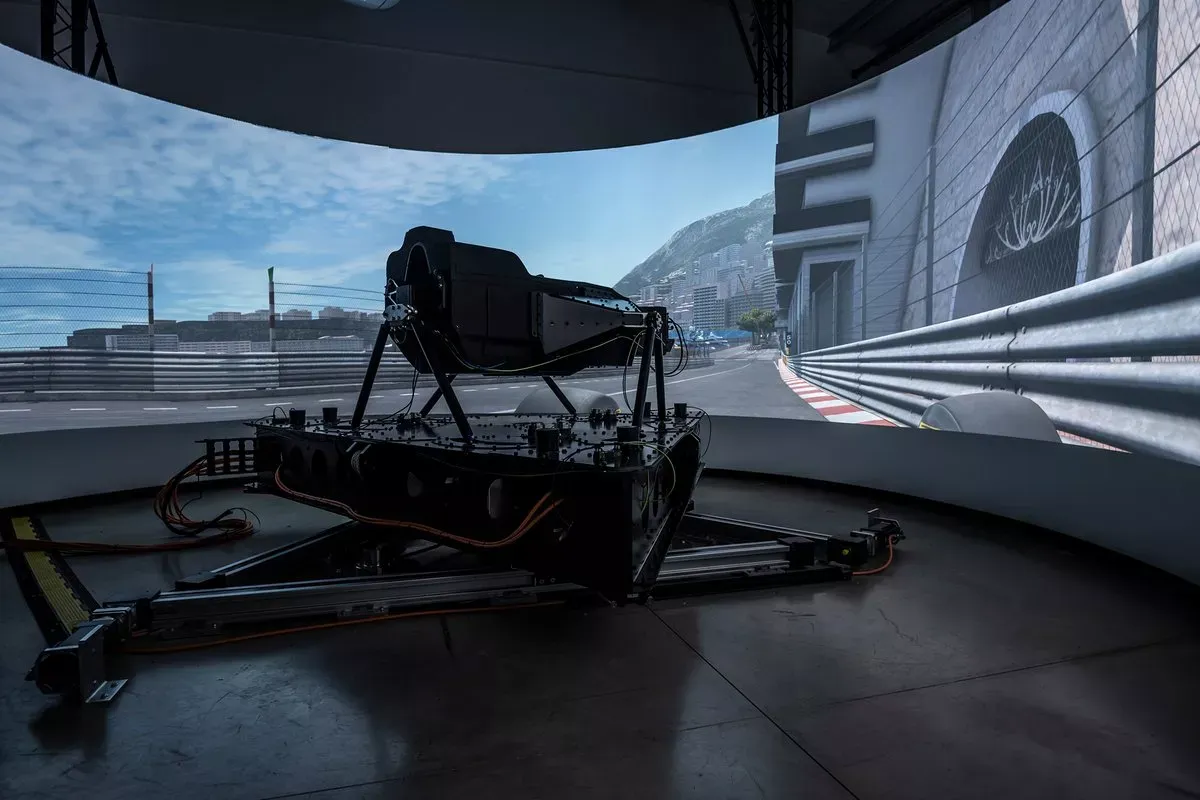

I've never hung on to the steering wheel of a car so much as I am now lapping Barcelona's Formula 1 track.

As the left-hand wheels touch the kerb on the flat-out run up to Turn 9, both the deep rumbling noise and the vibrations that rattle the cockpit smash your senses.

But there is little time to think about that, or even enjoy just how frickin' cool it feels (and sounds).

Eyes are already on the turn-in point for the right-hander and trying to perfectly hit the apex that is somewhere up near the crest of the hill.

Despite all that has been said over the years about the speed and brutality of driving an F1 car, nothing can quite explain in words how time blurs when you are on the edge.

The milliseconds your brain uses to judge how close to the apex you got when you turned in have already taken too long. Where you thought you were, is no longer where you are.

Turn 9 has already long gone. You've been spat out the other end of the corner and you are now darting over the exit kerb – again that buzzing sound and vibration rattling through you.

Still gripping the steering wheel tightly, you pick everything up again, ease off the kerb and start thinking about the next corner. Then rinse and repeat on and on.

The sensations, feeling, intensity and emotions of it all are very real, even if what I'm driving is not an actual Formula 1 car.

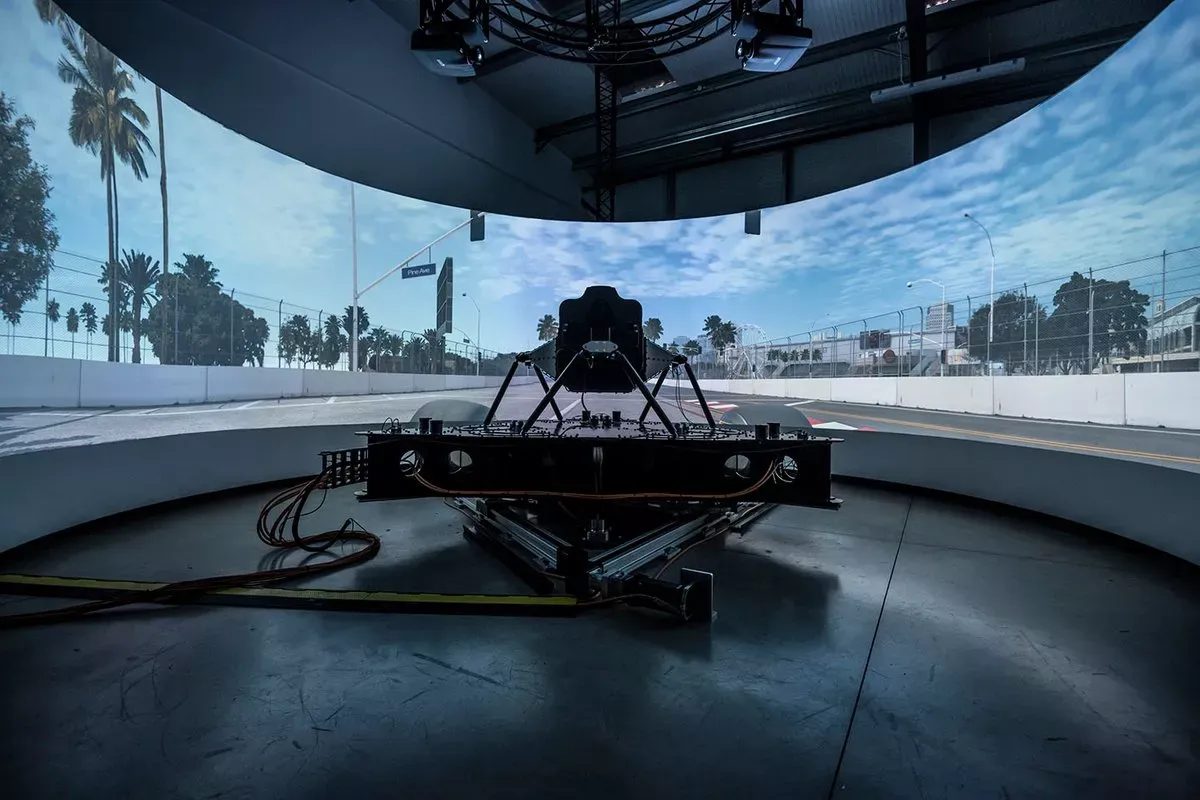

In fact, I'm nowhere near Barcelona. I'm in an industrial unit on the outskirts of Bristol, driving what is touted as the most realistic simulator that is commercially available.

The DMG-1, built by company Dynisma, is reckoned to be the second most realistic simulator in the world.

It's beaten only by the bespoke official Ferrari sim that Dynisma built exclusively for the Maranello squad itself. It's a company that knows its stuff.

When you talk about realism in racing simulators, the obsession is often about the graphics and how well the cars handle. Does it look nice and can I race well against the AI or my mates?

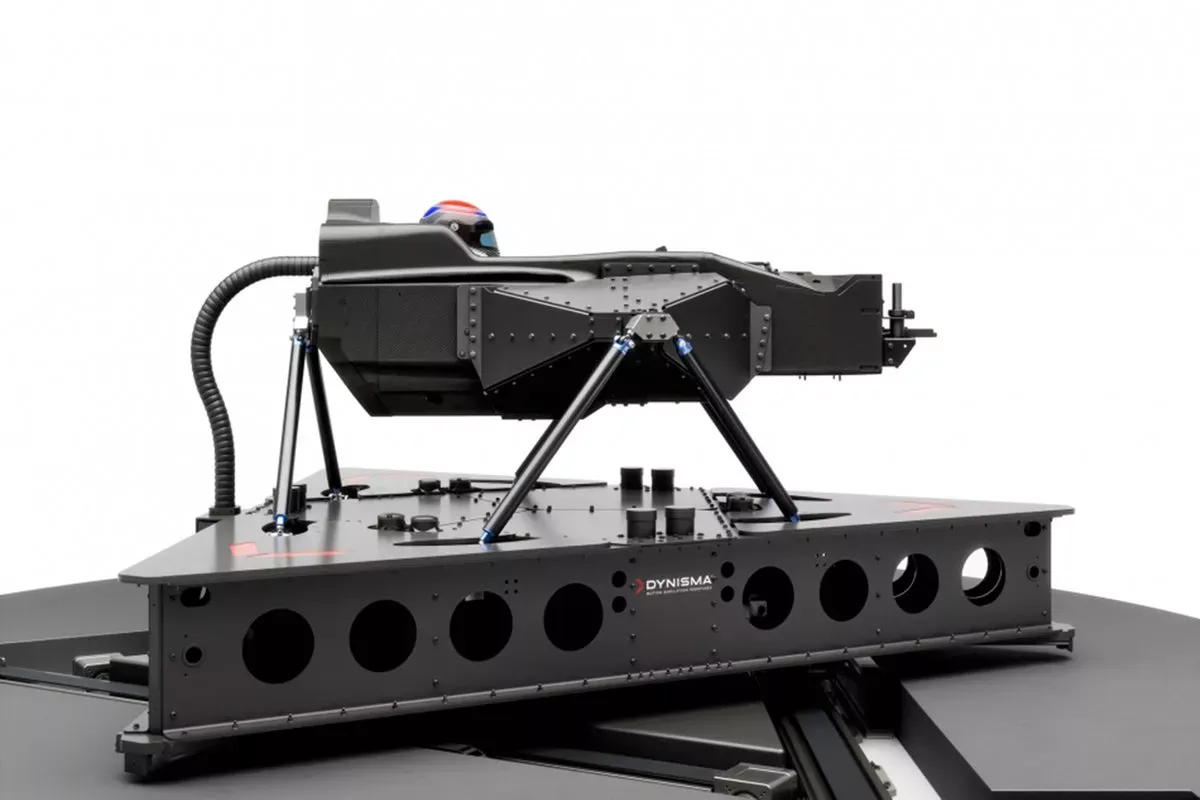

But when it comes to true realism in simulators – or motion generators as Dynisma's founder and CEO Ash Warne prefers to call them – graphics fall down the order for what is a priority.

What counts for it to be a properly effective tool for both drivers and the teams using them is their latency – which is the speed by which information about what the car is doing can be fed back to the driver for him to react.

If a handling model has the rear wheels losing traction and stepping out, but the driver cannot feel that happening quick enough to respond, then the car spins around unpredictably.

This information feedback is something that needs computing and getting processed to the driver, not in tenths of a second, but milliseconds.

In years gone by, it was felt that a latency of 20-50 milliseconds was deemed acceptable.

But the DMG-1 has taken things to the next level, getting latency down to under five milliseconds – which is ten times better than some other current simulators available on the market.

"It's a really critical parameter," says Warne.

He previously led the simulator team at McLaren and worked with Ferrari's previous generation model when he was there as a senior vehicle dynamics engineer before he set up Dynisma in 2017.

"A simulator is a very holistic system, bombarding all of the senses of the driver. But ultimately, what you're trying to do in a racing simulator, especially in high-performance racing simulators like F1, is get the driver to respond in the same way as they would in the real car.

"You have a very accurate vehicle model, which captures all the physics, but then you need a really high-end motion system like our technology, which provides that information to the driver as quickly as possible.

"Our motion system provides that feedback to the driver within three to five milliseconds, which allows them to respond instantly and catch any slides that may be occurring.

"What often happens on other simulators, which aren't as quick as ours, the driver tries to drive the simulator and they get some oversteer. And the back end just spins out because they haven't been able to catch it.

"They haven't had that oversteer cue, that movement, in time."

Having managed to catch a few rear-end slides myself – especially out of the low-grip final chicane at Spa, and La Source – I can attest that there is no delay in how quickly that feeling comes on tap.

It is something that F1 sim driver and Formula E racer Jake Hughes has noticed too when trying out the DMG-1.

"Instant is the word," he said after trying it out. "The initial yaw cue is very instant. Kerb riding feels good and very realistic. Even touching the apexes feels good in high-speed corners and also the tyre chatter with understeer."

The real value of this benchmark latency is not just for the drivers though, because it makes the simulator an even more valuable tool for teams that run it.

Setups can run as close to real life as possible, and that can fast-track engineering knowledge.

Without a low enough latency, and if the simulator car is spinning all the time, then its value as a tool is reduced.

As Warne says: "What they need to do is often dial understeer into the setup of the car, in order just to get around the lap.

"But then fundamentally you don't have correlation between the setup in the real world and on the sim. You're not conducting an accurate and representative test."

Critical also to the realism is the amount of bandwidth that a simulator can transmit. A few years ago, it was felt that 20 Hertz was good enough for engineering. The Dynisma DMG-1 runs at 100Hz.

Warne adds: "In the past, people talked about having a bandwidth of about 20Hz being enough.

"The reason for that was that if you go up to a car and you kick it, the body modes of the vehicle were somewhere between five and 15 Hz. So the thought was, why do you need a lot higher than that?

"In actual fact, all that suspension does is attenuate the frequencies that are coming through the car. You can still have much higher frequencies reach the driver, even on your road car.

"So when you go outside, and you drive over a rumble strip, these frequencies can easily be 100Hz, and you're feeling it straight through the vehicle.

"But there is also data that's coming from the vehicle model that tells you what the car is doing; whether it's tyre vibrations, whether it's the contact patch dynamics and drivetrain vibrations. All of this plethora of information is coming through from very low to very high frequencies.

"Every other simulator has got this filter on it, which dumbs everything down so it becomes this numb system."

There are other elements too that Dynisma says make the DMG-1 stand out. One of these is the lack of clunkiness, either mechanically or in sound, as it moves around when in action.

Having driven laps of Barcelona and Spa (and yes, I managed to take Eau Rouge flat!), the immersion in the driving was complete by the fact that it felt so natural and real. Nothing felt fake or unnecessarily exaggerated.

Warne adds: "The signal-to-noise ratio, so the data that we put through our simulator, comes to the driver without a whole load of other miscues and noise that you get on other simulators.

"When drivers test our simulator after trying others, one of the first things that we always hear is how mechanical everyone else's simulators feel: how they have clonks, bangs and rattles. Things that you obviously don't expect in an accurate simulation.

"We focused from day one on eliminating all of that stuff, and what we've got is a real pure motion generation device where, what the driver feels, is what we ask, and not a whole load of other peripheral noise."

Simulators have come a long way from when McLaren first believed they would be an essential tool in any team's armoury.

What's changed too is the fact that whereas once they were the exclusive domain of the mega-rich F1 squads, now teams at all levels can stand to benefit from them.

Dynisma has aimed its DMG-1 specifically at this market, offering a turnkey solution that can be adapted to suit any category at any level.

And the cost? "For one of our DMG-1 driving simulators, including the visuals, the computing, the vehicle models, the terrain models, it is in the region of £2-3 million," says Warne.

That's not pocket change, but, as a tool that is aimed at helping advance performance, and potentially making the difference between winning the losing, history shows that success in motorsport almost requires one now.

"McLaren were the first to show that a driving simulator could be a useful tool in developing a high-performance race car," explains Warne. "They basically de-risked it for everybody.

"Until that point, nobody really knew that you could develop an effective tool. And it gave everybody else the impetus to go and invest.

"But now they have been proved to be a really valuable tool for the development of a race car performance."

And, having been lucky enough to get behind the wheel of Dynisma's latest model, my tired arms and buzzing brain can attest that the realism levels are something else.