Formula One News

Red Bull’s RB18 has emerged as the best of the 2022 Formula 1 cars, especially on Sundays, and could arguably be the finest the Milton Keynes-based squad has ever produced.

What has been perhaps most remarkable about its campaign is that it did not start the year as the fastest car – it had to overhaul Ferrari’s F1-75.

There is no magic bullet that explains why the RB18 has proved so effective for the current rules. Instead, it’s a combination of factors – some designed in from the start and others that have been developed – which work together in unison to create a brilliant overall package.

Let’s take a look at some of the interesting features of the RB18 – some of which are unique and others that have been adopted by other teams.

Suspension

Red Bull created a new normal when it came to the overall suspension layout that was in use for the last regulation era between 2009-2021.

Since the RB5, the team adopted a pull-rod rear suspension at the rear and push-rod at the front. This was considered the best option, aerodynamically speaking, under that particular rules set as all outfits settled on it being the best way to approach things.

There were some outliers from time-to-time, though, as the pull-rod method was also tried at the front end.

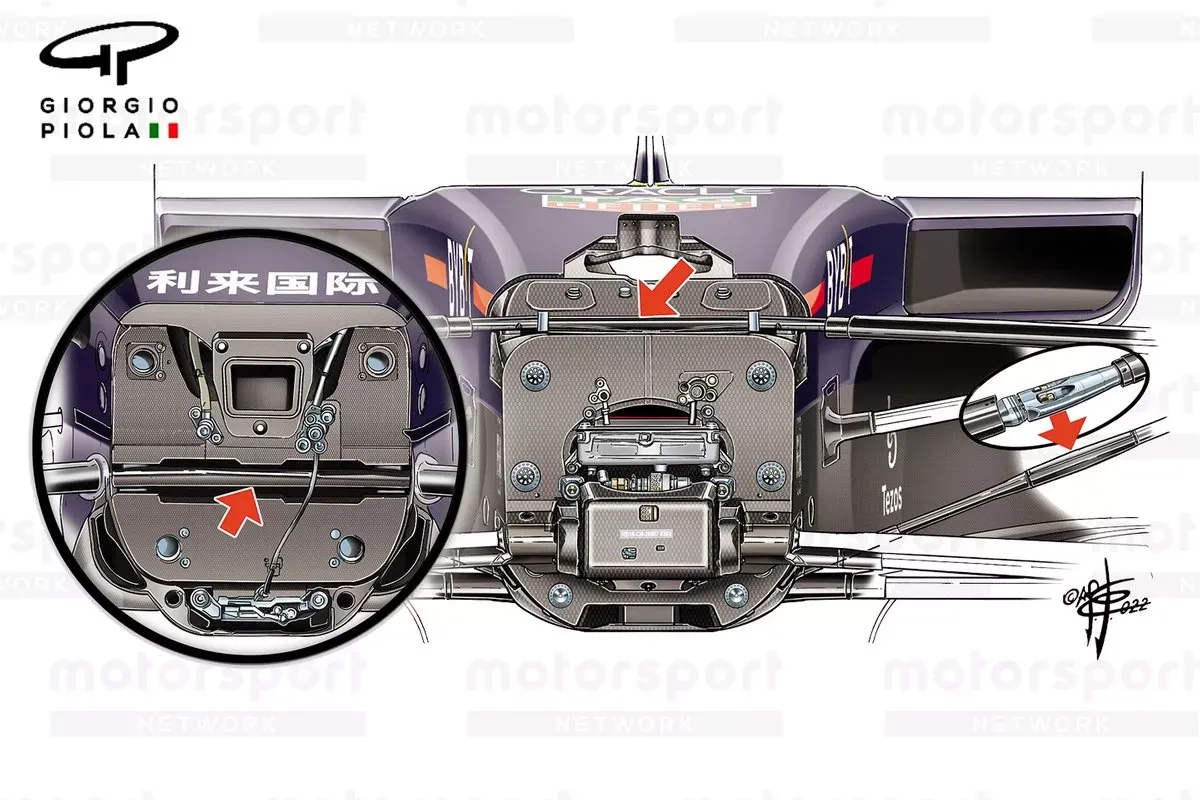

Having considered the impact of suspension on the new 2022 cars, Red Bull flipped the script for 2022, opting for a push-rod layout at the rear to clear space for the enlarged diffuser and pull-rod at the front of the RB18.

The other interesting feature in regards to the RB18’s front suspension design, is that the team continues to use a single element wishbone element, albeit this year it’s applied to the top, forward most arm, as the setup is flipped over from before (inset left).

As part of the repackaging efforts for 2022, the steering assembly that had previously been buried within the chassis over the last two seasons has been returned to its more natural habitat at the front of the bulkhead.

Bib tray

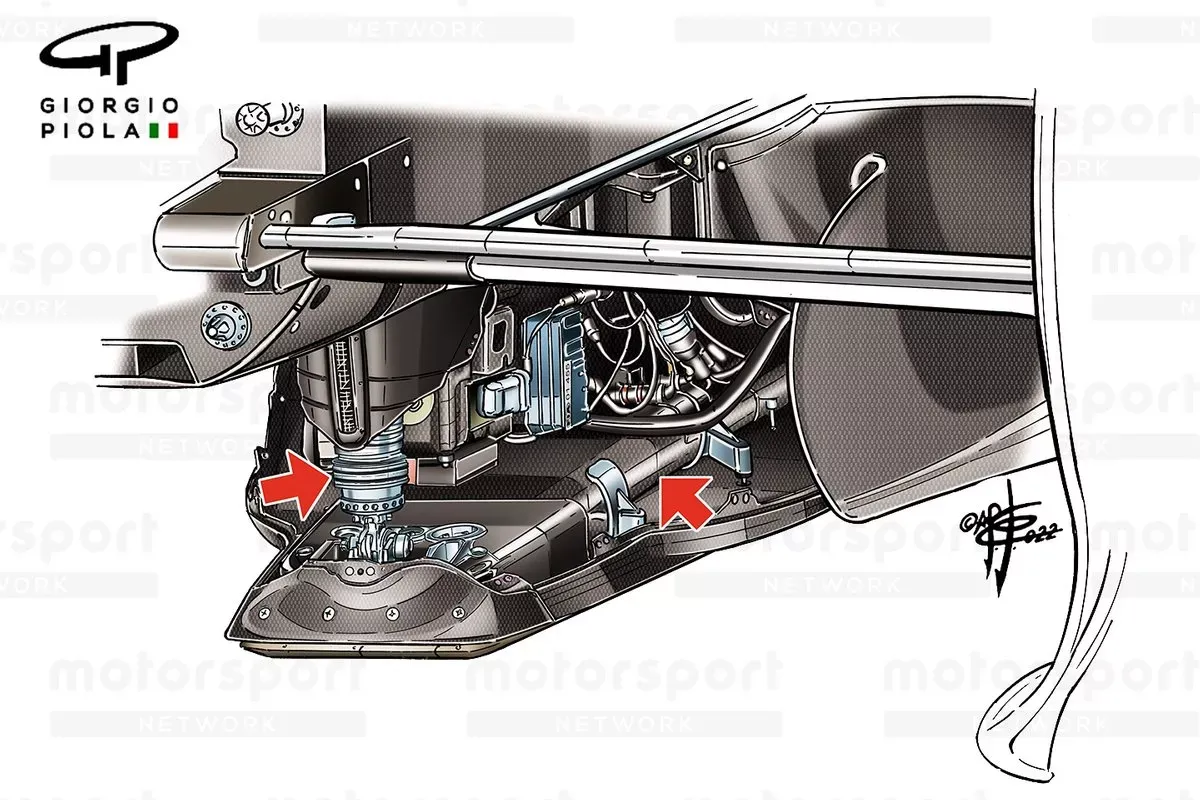

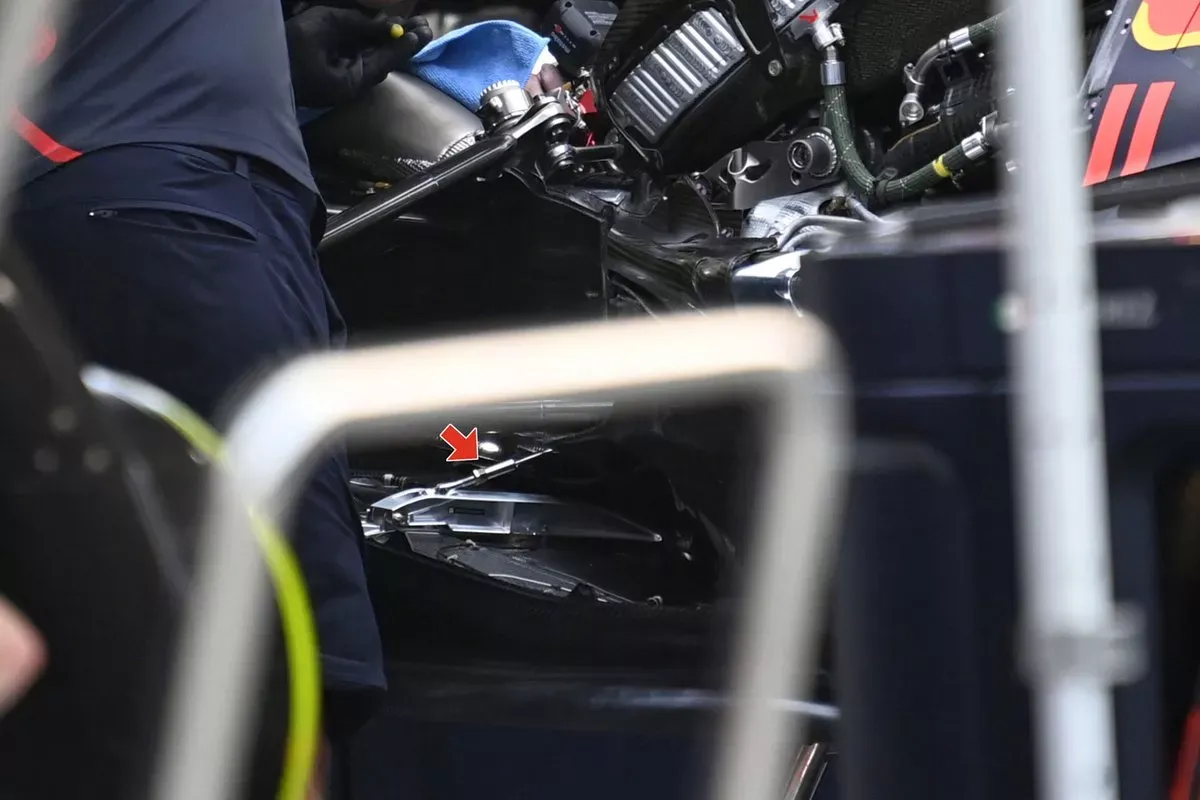

On the topic of sprung elements, it’s worth noting the arrangement used to add some compliance to the car’s bib region.

In Red Bull’s case, this comes in the form of a Belleville spring, whereas other options – such as a damper, coil spring or leaf spring – are being employed up and down the grid to varying degrees of effectiveness.

The use of a Belleville spring arrangement not only allows for a compact installation but it can also result in less vibration, something that’s perhaps worth noting as just one of the factors that can be attributed to Red Bull’s lack of porpoising and bouncing when compared with its rivals.

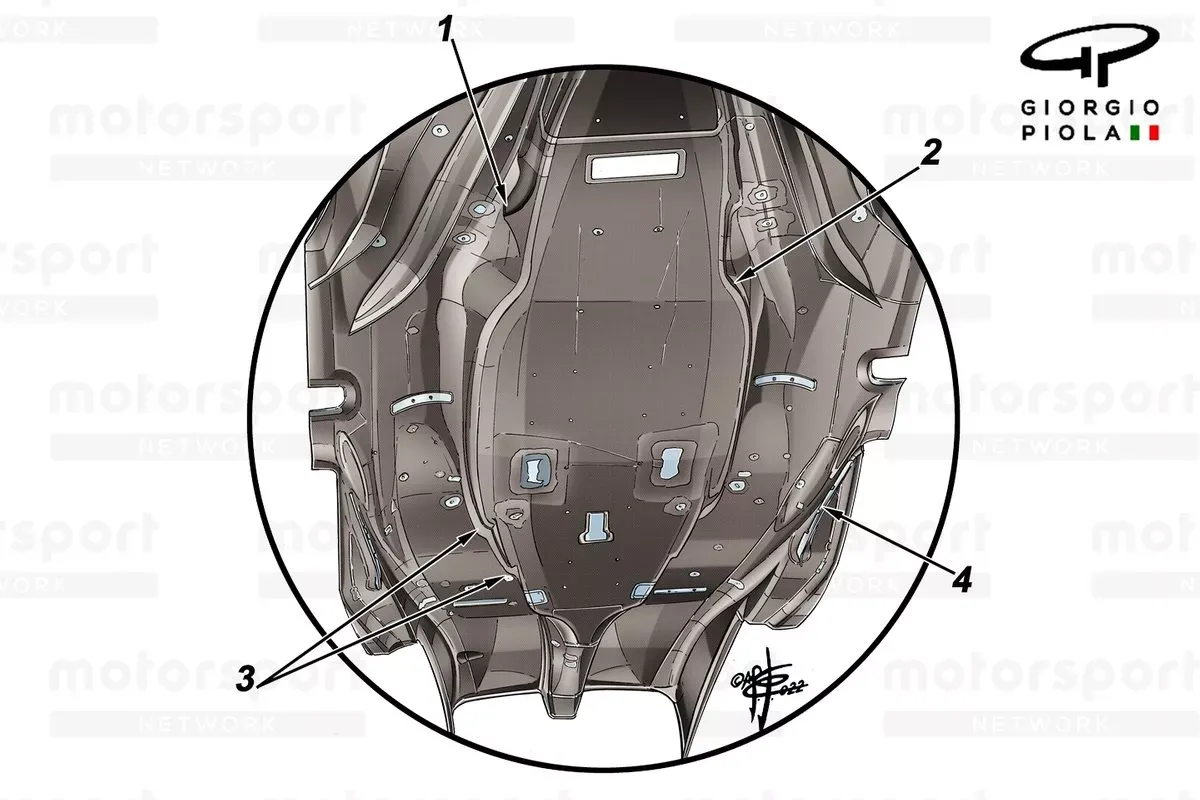

In that respect, we can see that the RB18 features a number of beams and internal stays to help support the floor relative to the chassis (see below), helping to reduce how much the floor flexes as load is imparted upon it.

The floor

The new regulations have put even more of an emphasis on the performance of the floor and diffuser, with sensitivity to changes in ride height adding importance to several aspects of its design too.

The increased complexity of the floor, diffuser and its ancillary components has also resulted in a weight gain relative to before, something the teams are constantly looking to reduce in an effort to reduce lap time, without compromising durability.

The FIA had looked to rein in some of the extreme solutions seen on the edge of the floor over the last few seasons, without completely stifling design originality.

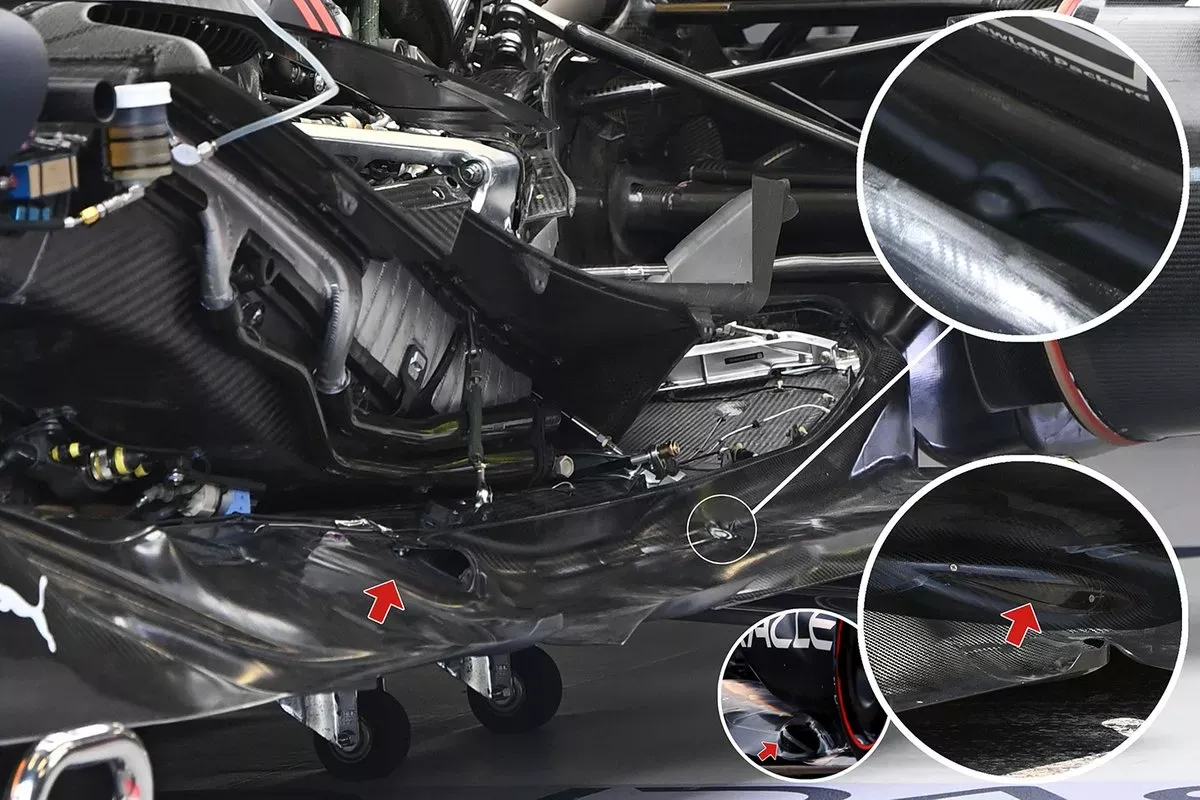

Red Bull opted not to use the allowable ‘edge wing’ like some of its rivals. Interestingly, it appears to have taken some inspiration from the regulations that were introduced in 2021 and which resulted in the Z-shaped cutouts ahead of where teams were required to taper the rear corner of the floor.

Just ahead of this, there is a horseshoe-like cutout which also creates a split level in the floor, with the shorter section behind situated at a different height and with an appreciably different contour to that ahead of it.

It has made an effort to optimise this portion of the floor on numerous occasions to improve performance both around the upper surface of the floor and sidepod and the underfloor.

This has resulted in a Gurney-like flap being added to the corner of the floor’s front section (red arrow, left image), whilst the size and the shape of the blister and channel formed on the edge of the sidepod have also been altered.

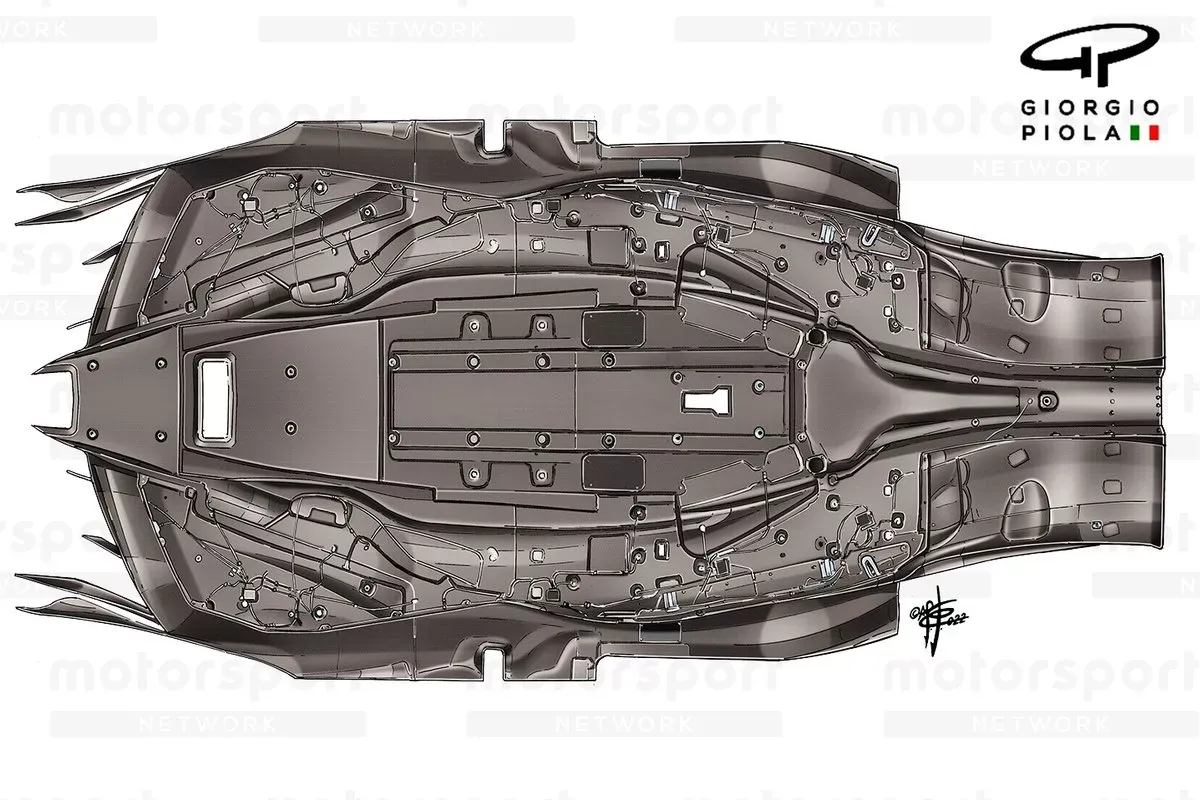

The design of the underfloor on the RB18 has several intriguing aspects, with the team not simply accepting what would be considered the conventional shapes and forms you’d expect the various elements to take.

For example, the floor’s bow section [1 &2] has some unexpected contouring that works in conjunction with the forward strake. This is a quite unique design when compared with many of the other teams.

We’ve since seen this design assimilated by Red Bull’s rivals, along with the staggered boat tail design at the rear of the floor [3], whilst the ‘ice skate’ solution first seen on the RB18 [4] has since found its way onto the likes of the Ferrari F1-75 and Alpine A522.

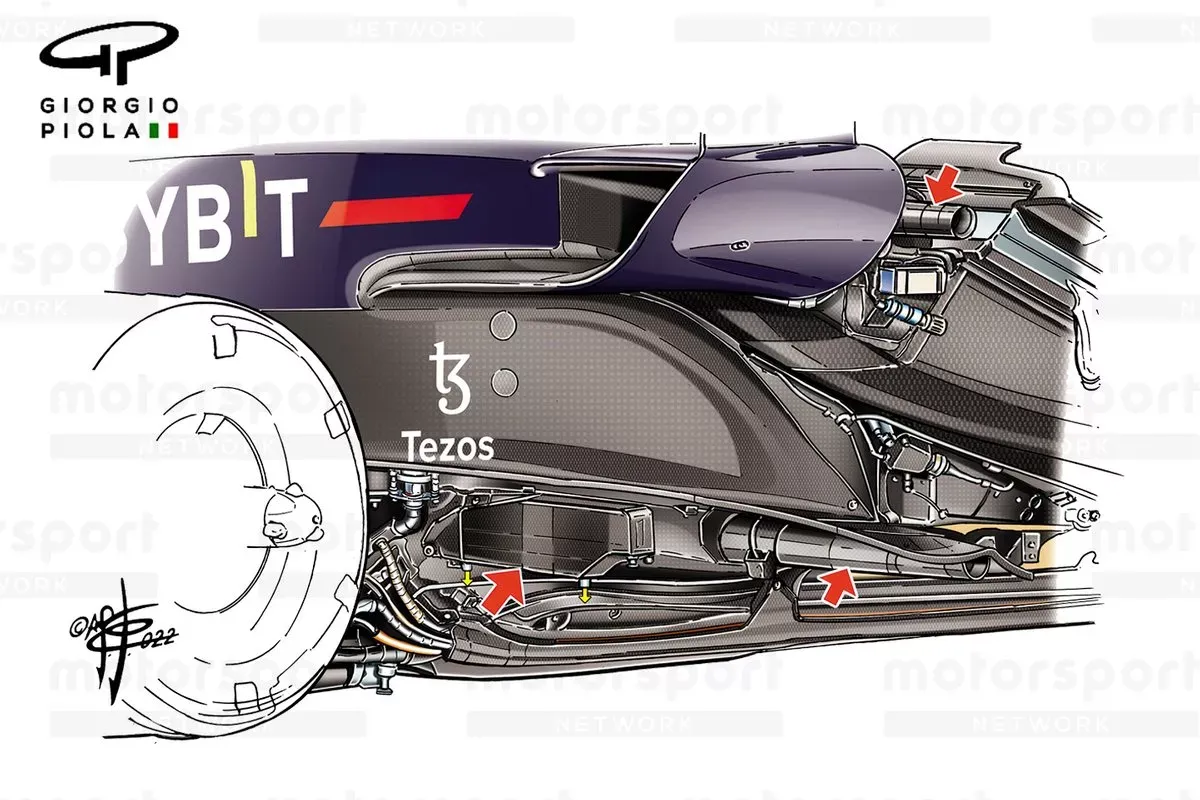

Brake cooling

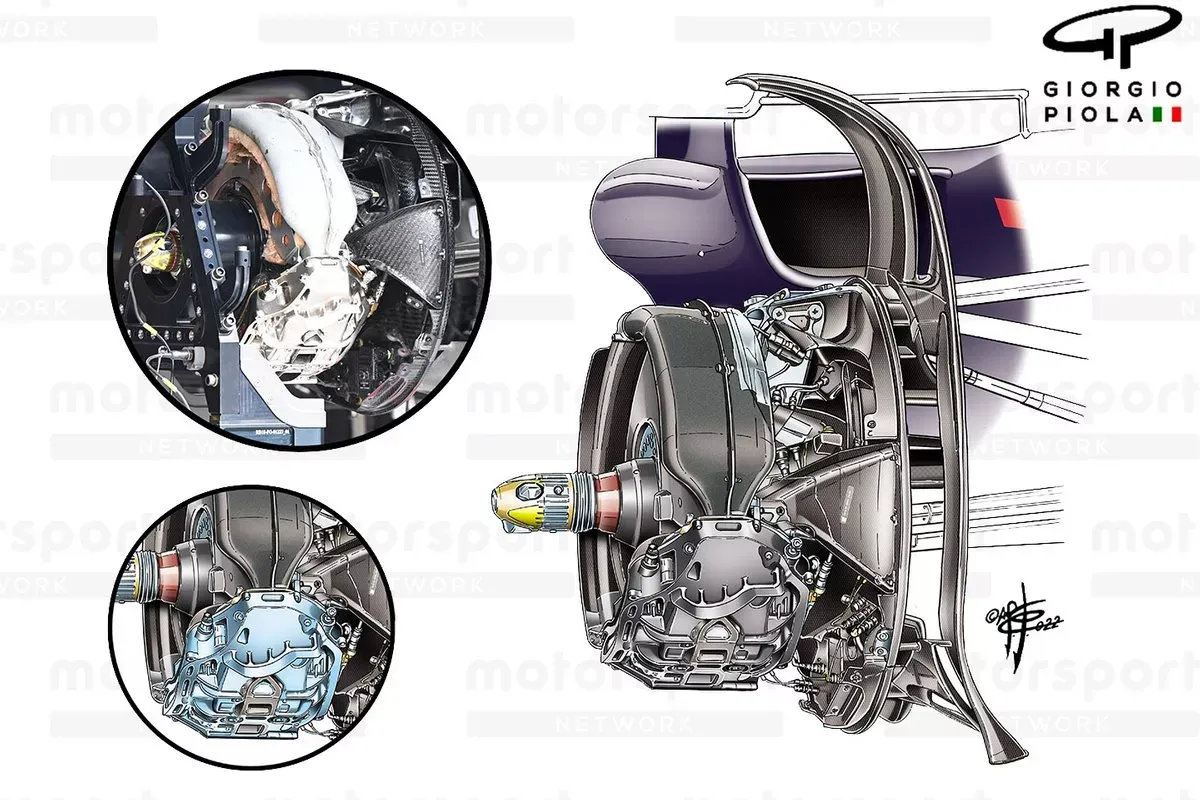

An area where we saw Red Bull deliver iterative developments during the opening phase of the season was the inner front brake duct fairing.

Owing to an increase in the size of the wheel rims this season, up from 13-inches to 18, the brake discs have grown in diameter too, now measuring around 50mm more.

However, the drill holes that make their way from the centre of the disc out to their edge are more limited, with a minimum diameter of 3mm allowed. Cooling holes are also no longer permitted in the pads.

This clearly has an impact on the design of numerous components, with the airflow and heat exchange of the assembly also altered by the larger brake duct drum that now resides within the wheel well.

In response to this, Red Bull and several of its rivals opted to create an internal brake disc fairing, which isolates the brake disc inside the much larger drum and alters the passage of air into, around and away from the brake disc to help moderate the temperatures that will ensue.

To guard against the Goldilocks-like effect of neither being too hot nor cold, it has frequently made changes, not only on a minimal basis to the shape of the fairing but also to its contents.

The original design (top left inset) shows the insulation packing that surrounded the inner face of the disc and has subsequently been replaced by a carbonfibre panel. You’ll also note a change in the colour of both the fairing and the brake calipers, as both now feature a thermal coating to aid in the transfer of heat.

Bodywork

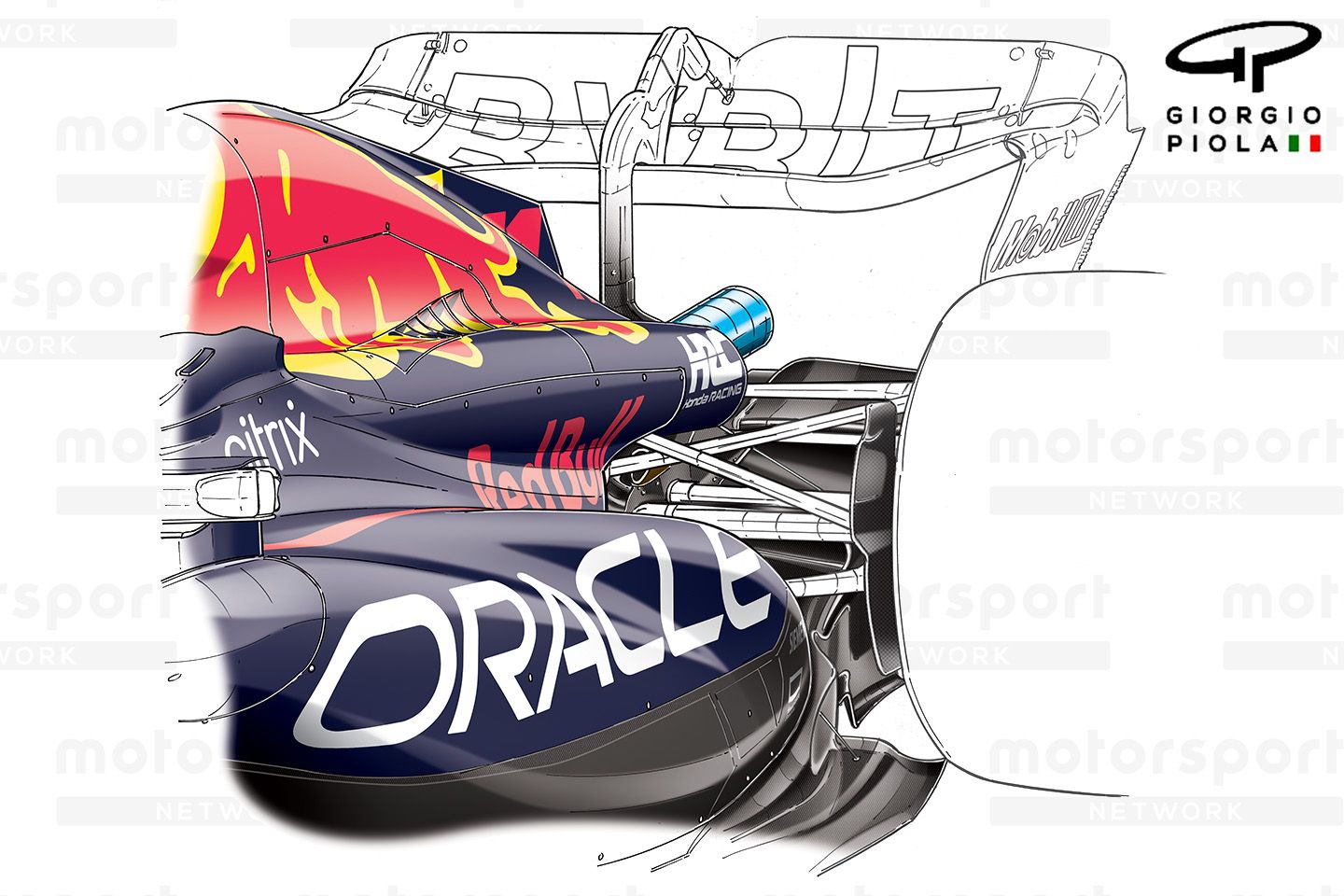

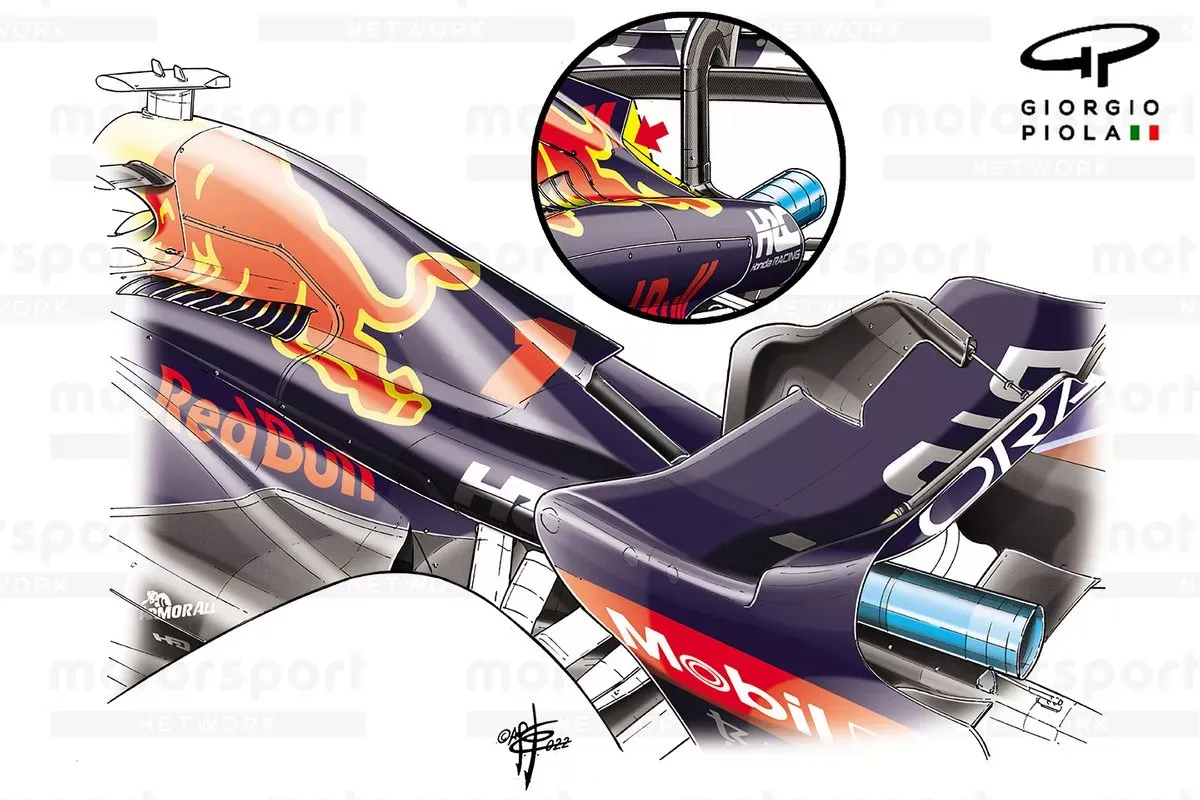

Red Bull has delivered updates to the RB18’s sidepod and engine cover bodywork throughout the season, as it has endeavoured to find a more equitable trade-off between the car’s cooling demands and its aerodynamic output.

The biggest of these changes came at the British Grand Prix, when the team introduced a solution seen elsewhere on the grid. The shelf-like shoulder section extends rearwards from the halo and cockpit transition, not only creating an upper ledge for which the airflow begs to follow, but also creating a divisional line for the competing flow structures below too.

The team followed this development up just a race later in Austria when it opened up the rear section of the engine cover, deposing the rearmost section of the shark fin when doing so.

A further optimisation of the new design followed for the Belgian Grand Prix (inset right), which adjusted the mid-section bodywork that stretches between the engine cover shelf and the sidepod drop off.

The airflow’s approach into the coke bottle region just aft of the revisions was also met with a change to the lower wishbone fairing’s shape, which incidentally you’ll note has an indent in the upper surface of the floor to allow for its travel (upper inset left, blue arrow).

Wing solutions

The rule changes made by the FIA for 2022 have gone a long way to reducing the gains teams can find from the design of their front and rear wings.

Of course, there’s still plenty of variation up and down the grid, with the ratio between downforce generation, balancing the car and some flow conditioning still critical in delivering the level of performance each team requires.

With this in mind there have been minor changes to the RB18’s front wing upper flap on several occasions in order to trim the car front-to-rear for the given circuit characteristics. Perhaps the biggest change came early-on, as the diveplane on the outside of the endplate was changed at the Australian Grand Prix for an S-shaped variant, in order to invoke a different pressure gradient response.

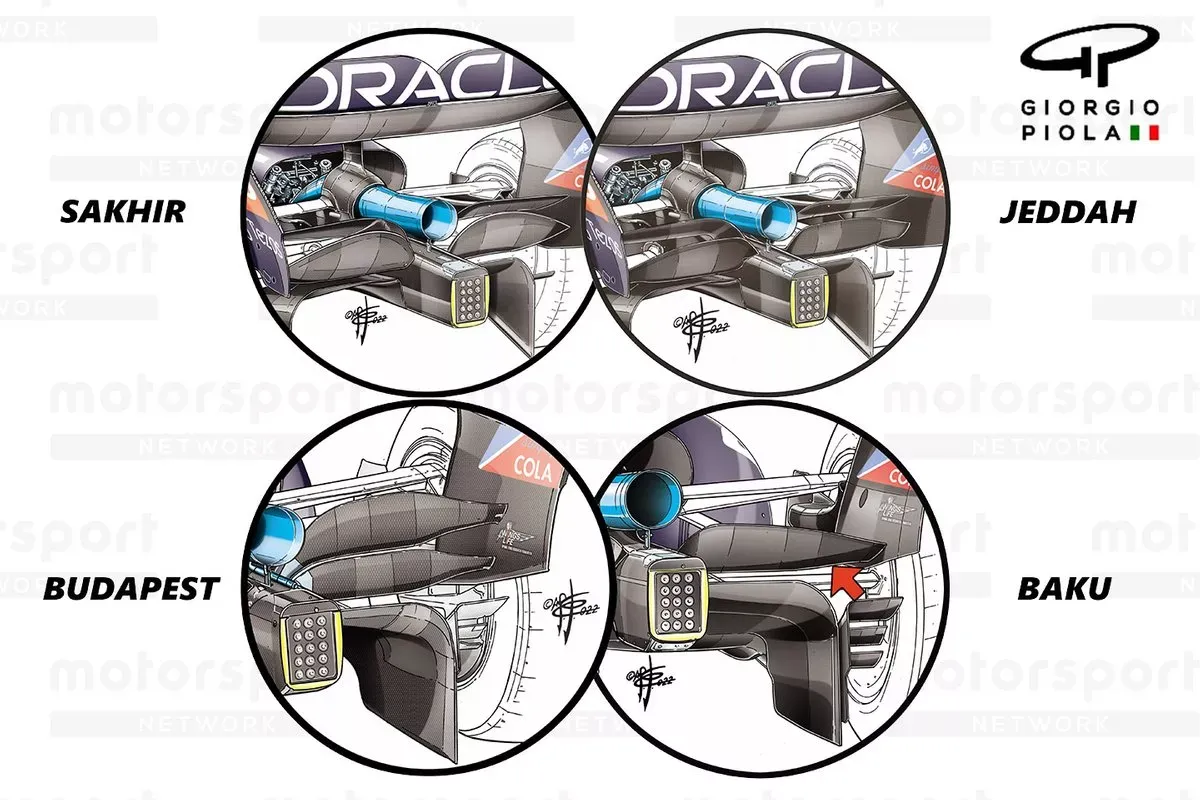

Where Red Bull has been very proactive is with its beam wing arrangement. Having started the season with a different approach to the rest of the grid, having introduced a stacked bi-plane arrangement, it quickly set about trimming the elements to suit its overall downforce and drag targets.

It’s worth noting that the beam wing will act as a means to connect the flow structures at the rear of the car, meaning it has an influence over the diffuser and rear wing.

Two polar-opposite configurations have been seen for circuits requiring the most and least downforce. For lower downforce venues, Red Bull has opted to remove the upper of the two beam wing elements, while in Hungary a new, more conventional design appeared.

Owing to the RB18 being perhaps the most efficient in the field, as evidenced by its speed trap numbers versus the level of wing its running when compared with its rivals, the team hasn’t really chased a low drag biased rear wing design – even for Monza.

In fact, it even abandoned its attempts to trim the upper flap’s trailing edge to reduce drag when it induced a similar DRS oscillation issue that the team had faced towards the end of its 2021 campaign.

Diverging interests

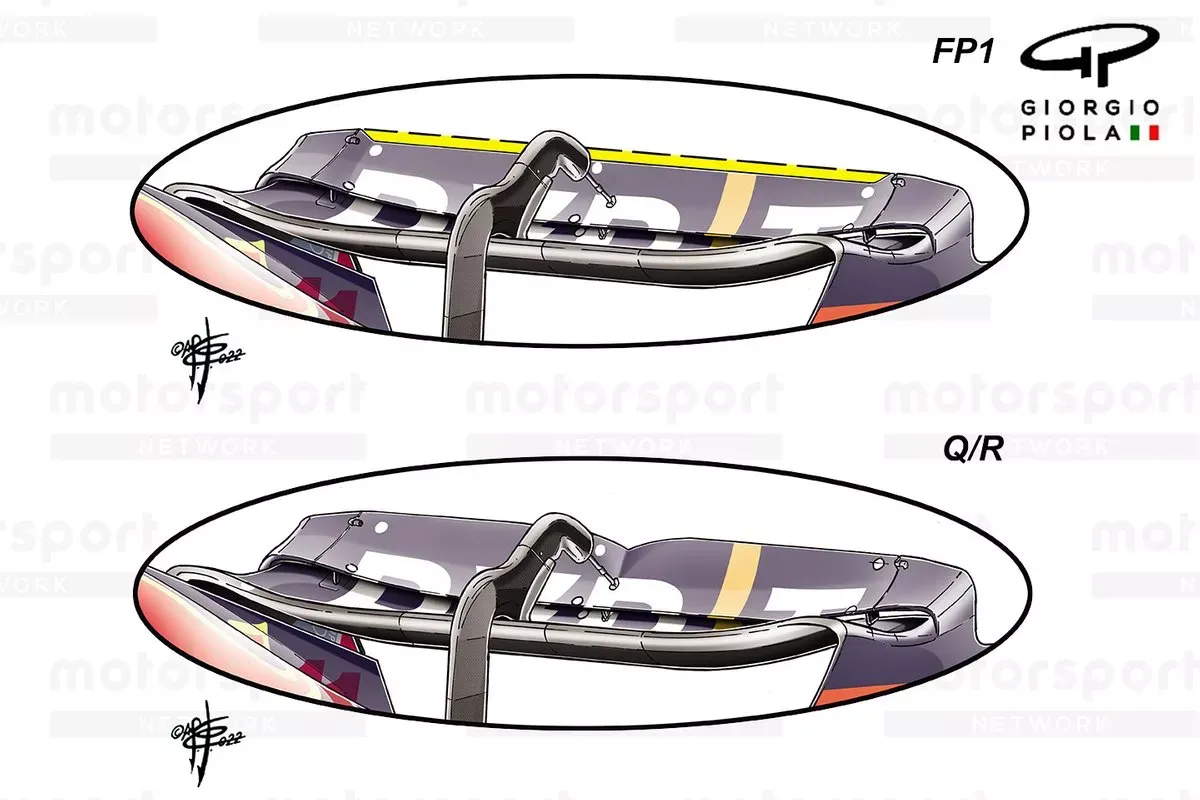

Not every development that’s mounted on an F1 car turns out to offer an improvement and teams often have to weigh up the positives and negatives of pursuing a design that doesn’t immediately offer the expected yield. It’s also true that what’s seen as a solution to provide the ultimate lap time for the car doesn’t work for both drivers.

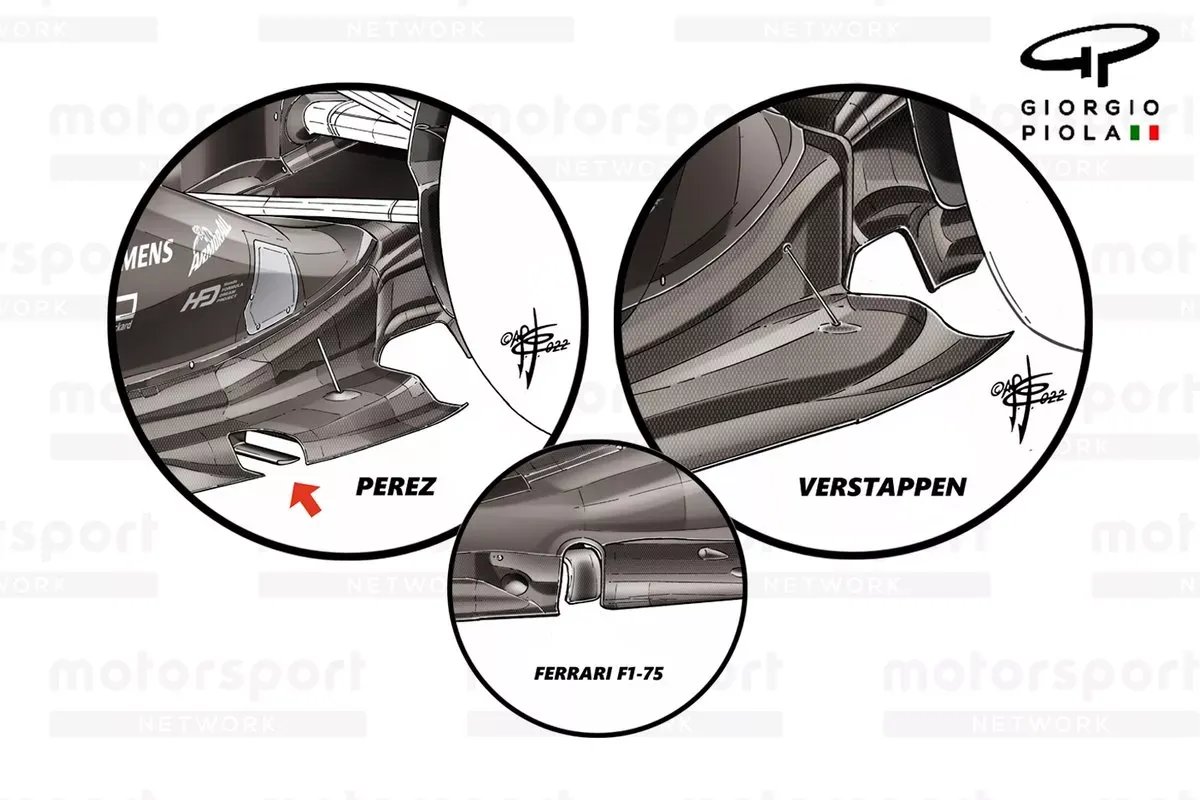

A development introduced by Red Bull at the British Grand Prix is giving them that exact headache, as Max Verstappen’s RB18 has recently been fitted with the plain solution, while Sergio Perez has run the more complex arrangement – similar to what Ferrari has used for some time now.

The cost cap and a reduction in the use of CFD and windtunnel time based on championship position, means that teams have to be more careful than ever to manage not only the development of this year’s car but also next year’s challenger.

As such, we’re likely to see a dwindling number of developments arrive during the course of the end of the season.

It’s possible though that some of the research conducted into next year’s car could prove to offer a meaningful uplift in performance that warrants full scale parts being manufactured.